Nurturing Boys: Holistic Parenting to Raise Loving, Well-Rounded Sons with Dr. Shelly Flais

About this Episode

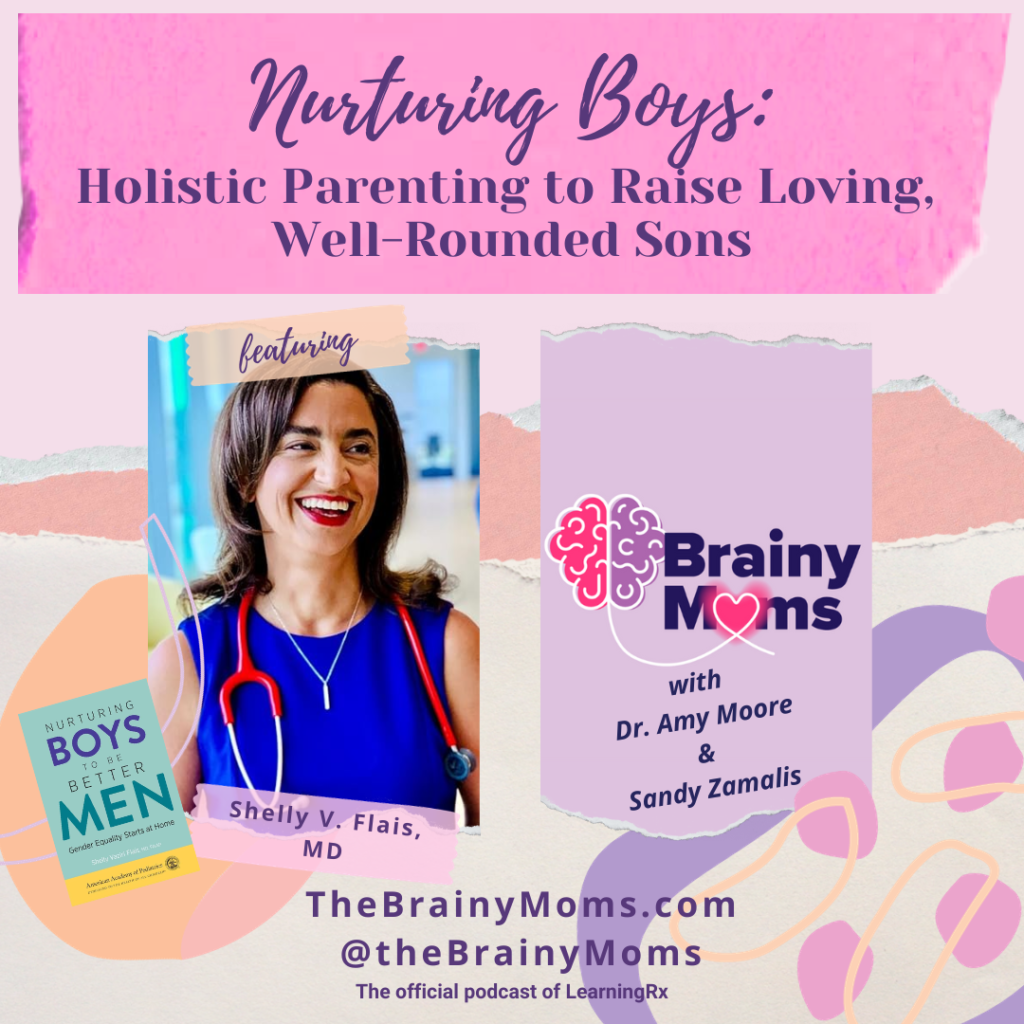

Are you tired of hearing people say, “Man up!” or “Boys will be boys” around your son? Or perhaps you’ve seen boys discouraged from liking the color pink, learning to cook meals, or expressing feelings of sadness or disappointment. If you’re ready to break generational stereotypes and raise well-rounded boys who will grow up to be well-rounded men, you won’t want to miss this episode. Dr. Amy and Sandy are joined by guest Dr. Shelly Flais, author of “Nurturing Boys to Be Better Men: Gender Equality Starts at Home,” who shares her experience as a mother of three boys and practicing pediatrician.

About Dr. Shelly Flais

Shelly Vaziri Flais, MD, FAAP is a board-certified practicing pediatrician, the mother of 3 sons and 1 daughter, and Assistant Professor of Clinical Pediatrics at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago. She is the author of “Raising Twins,” Editor in Chief of Caring for Your School-Age Child, and co-editor of “The Big Book of Symptoms.” She is an American Academy of Pediatrics spokesperson and frequent media contributor who lives in the Chicago suburbs. Her new book, “Nurturing Boys to Be Better Men: Gender Equality Starts at Home” will be published October 24, 2023.

Connect with Dr. Shelly Flais

Facebook: @ShellyVazirFlaisMD

Instagram: @ShellyVazirFlaisMD

Twitter/X: @ShellyFlaisMD

Book: “Nurturing Boys to Be Better Men: Gender Equality Starts at Home” (Oct. 24, 2023)

Listen or Subscribe to our Podcast

Watch this episode on YouTube

Read the transcript for this episode:

DR. AMY: Hi, smart moms and dads. Welcome to another episode of the Brainy Moms podcast. I’m your host, Dr. Amy Moore, coming to you today from Colorado Springs, Colorado, and I am joined by my co-host today, Sandy Zamalis. We are super excited to welcome our guest today, Dr. Shelly Flais. Dr. Flais is a board-certified practicing pediatrician, the mother of three sons and one daughter, an assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, and Anne and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago. She is the author of “Raising Twins,” editor in chief of Caring for Your School Age Child, and co-editor of “The Big Book of Symptoms.” She’s an American Academy of Pediatrics spokesperson and frequent media contributor who lives in the Chicago suburbs. And she’s here to talk to us today about her book, “Nurturing Boys to Be Better Men: Gender Equality Starts at Home.”

SHELLY: Thank you so much for having me. It’s great to be here.

DR. AMY: Yeah, we are really excited to talk to you about this topic. I actually am a mom of three boys. No girls, just three boys, and so I assume that part of your interest in talking about gender equality in boys stemmed from also raising three boys, but maybe also from your work as a pediatrician. Talk to us a little bit about why you’re so passionate about this topic.

SHELLY: Well, really, I’ve worked on this book in earnest the past three, four years, but it’s really been 22 years in the making. My oldest is now 21, and when he was 18 months old, I had twin boys. We thought it’d be fun to have kids close together in age. My older brother was 13 months older than me. He’s my best friend. So I always wanted that for my own family. I never planned on two minutes apart. And when I realized that I was going to be a mom to a brood of boys, something about their arrival together got me thinking. Working in a historically male-dominated profession, I was surprised at how we have come far, but we still have more to go. When I was a little girl, I always wanted to be a physician. It never occurred to me that it would be a juggling act to be a physician and a mom at the same time. Fast forward to present day, turns out it is still challenging. And so the question, as a pediatrician seeing newborns through college, I have the fortunate ability to see kids of all ages at all times, and I very much connect decisions we make at early stages with how things pan out 10 years down the line, 15 years down the line, and decades later, and so it really got my wheels spinning. You also turn on the news and hear about current events, toxic masculinity. And I can’t control what happens out there, but then here we have these young boys in our homes. Everyone is someone’s son. So what are the decisions that we can make even as early as pregnancy that can make an impact? So it’s a subject near and dear to my heart.

DR. AMY: Sounds like it for sure. Sandy was like, “I’m going to cry during this episode.” She said, “I feel so strongly about this.” And I was like, I’ve never seen Sandy cry.

SHELLY: Well, and to that end, you know, there’s a lot of expressions. The book kind of goes ages and stages. It goes chronologically so busy parents don’t have time to read a 300-page book. So they can kind of, “We’re pregnant. Let’s look at this chapter. Our son is five months old. Let’s read this chapter.” But then in each section, there are phrases that do us no favors.

And so “boys will be boys” or “boys don’t cry.” And I always tell the story and I share the story in the book. There was a tennis match. I can’t remember which of the Grand Slam tournaments it was, but Serena Williams had just gotten back from having her first child. She had a lot of medical complications. There was a referee that was making some questionable calls and she got upset and was challenging the referee. My three sons and I were watching this in real time. And somehow my interpretation—it’s so interesting when something is playing out, how we all approach it from our own vantage point. In live, on live TV, Serena was arguing with the referee and you could tell she was getting upset and I kept, and I started to say out loud, “Please don’t cry, please don’t cry,” because I felt like she represented working moms everywhere, going back to the workplace and having a challenging situation. And my son said to me, “Why can’t she cry? She’s human. She feels very strongly about this issue.” So to my then teenage sons, they were like, “Of course she can cry.” So I was having the old-school thought of “No, no, no. It’s a, it’s a sign of weakness, you know, show your strength. Don’t cry yet.” Here we’re teenage boys saying it’s okay if she cries. And so then I was really crying at that point because I thought I never even thought of it that way. So whether it’s a man or a woman, just to hear that perspective and that definitely writing a book like this is very humbling and. I very much am coming at it from a humble space, a growth mindset. I’m by no means perfect and have all the answers, but there’s situations, scenarios that we can all do better. And so, but that was a moment that I was like, “I’m doing okay.”

DR. AMY: Absolutely.

SHELLY: We’ll just start with crying. How’s that for positivity?

SANDY: And the reason I said that is because, you know, I just feel so strongly. I only have one boy, but I just feel so strongly that, in general, I feel like the world is hard for boys and has been for quite a long time. So I just get tender-hearted over this topic, but let’s talk about your book. You have, one of your main goals is to have a roadmap to promote greater generational, gender equality in our homes. So I’d like to start with that first goal, which you say is promoting a whole-child approach like you just talked about and recognizing our sons as capable of the full range of human emotions despite generational perpetuation of the idea of male characteristics. Can you explain for our listeners what you mean by “male characteristics” and how the journey to this goal might look for parents and society at large?

SHELLY: That’s the million-dollar question, right? And we as parents might have certain goals in mind, but then we launch our sons into the world. And so even though within our homes, we have certain goals and belief systems, they’re going to school, they’re interacting with the community, they’re going to youth sports. And very quickly you see what’s out there. And as early as third, fourth, fifth grade, often society’s putting boys into a box. The “boys don’t cry” box. The “be a man, tough it out, be independent. You don’t need to talk about your feelings.” Even how many times we’re all here, moms of boys. How many times have people told you, “Oh, boys are so easy. You have it easy.” How are boys easy? How is it easier having a boy than a girl? I feel that does our sons a disservice. So the, the general thinking out there is that girls are communicative, talk about their feelings. To these parents, perhaps too much so, but shouldn’t our sons talk? Shouldn’t our sons share their feelings? I feel that if you feel that boys are easy, then you’re doing it wrong because they need to explore their inner lives. And absolutely different people communicate in different methods. And part of that is meeting your child where they’re at, learning their communication style. Knowing that after a hectic school day, perhaps followed by extracurriculars, simply as a parent asking, “How was your day?” But you’re going to get crickets. You’re not going to get anything. First of all, kids need time to zone out and maybe just kind of regroup on their own, just like we adults do. But then the best conversations I think happen when you’re doing other things. So those car rides are huge because the eye contact, your eyes are on the road. Somehow it’s easier to have those communication, that kind of communication. So, and then in an ages-and-stages approach, role modeling, what are, what we want to see our kids do in the future. And so that begins as early as infancy with paternity leave, maternity leave. How often are moms taking X weeks and months off, but then dads rush right back to work? Now, a big problem in our country is, compared to the rest of the world, we really don’t have protected paternity leave. And even for the companies, in my research I learned that even for the companies that do offer it, it’s, there’s a culture kind of frowning upon it, that you’re not going to get promoted. There’s a social stigma to actually taking the leave that you’re entitled to. It also varies greatly state to state. California, for example, is way ahead of the rest of us. But in infancy, changing diapers, burping your baby, feeding your baby, these are all very important stages for connection that sets the stage. And if we have a chunk of time where the female parent is doing everything, it kind of sticks like Velcro and then the mental load of running a household then falls to the female parent, which is not necessarily healthy for anybody. And there’s going to be realms that are 50/50, there’ll be realms that are 70/30, some will be 30/70, but there’s got to be that balance. So yeah. Clearly, I have a lot to say about it.

DR. AMY: So it’s interesting. I want to dig in a little bit about that. My husband was always 50/50 from the day. You know, our, our kids were born except obviously when I was nursing, he couldn’t feed them, but he would get up in the middle of the night and go get them out of their crib, bring them to me. I didn’t have twins. I’m talking in plural. Bring the baby to me, let me nurse the baby and then take the baby back to bed. And so he’s like, “If you have to be up to feed him, I’m going to help.”

SHELLY: I love it.

DR. AMY: Yeah. He was amazing that way. And he was active-duty military at the time we were still having kids. And so he was able to take several weeks off each time we had one and just really be fully present and engaged in all aspects of having a newborn. It never occurred to me that that was setting the stage for something developmentally for our children.

SHELLY: Oh, and I see it in my practice all the time where the early appointments for a newborn, mom and dad are both there. But then as time goes on, dad’s back to work, then it’s mostly the female parent bringing the child to their appointments. Or something I hear a lot, we do a two-week weight check, a one-month visit. Families get sick of us when the baby’s new because we pediatricians are checking on them every two minutes. Often they’ll talk about overnight feeds and it’ll come out in conversation like well, I handle those feeds because he’s got to go to work the next day. And over the years, I’ve developed a system of, you know, record scratching on the needle scratching on the record like, “You are very much working the next day also, whether it’s paid labor or unpaid labor. You are working just as hard.” So that concept of like, I have to go to work doesn’t fly to me. And sometimes parents hear this in 2023. I said it last week and parents are like, “Oh, you’re right.” And I think that’s part of the challenge. Parenting is hard. We are in the trenches, especially when you have a newborn. You’re up, you know, three, four times a night. We are just trying to get through each day. And so then to think about these big-picture goals during the day to day, that was one of my goals of the book, like kind of a playbook. “Here’s some practical daily steps to apply to reach your big-picture goals.”

SANDY: Oh, that’s really interesting. So I know we’re talking about our boys, but this involves our husbands, right?

DR. AMY: Well, there are boys too, right?

SANDY: Right. But, you know, this is a pre conversation before kids and maybe even hard conversation after kids. So Dr. Flais, do you have like recommendations on how to have those tough conversations? I, you know, I love my husband and I don’t want to throw him under the bus at any, by any means, but he was a go-back-to-worker. And honestly, I was going to go back because, you know, having the baby was, you know, an anxious kind of thing anyway. And I could, I just did better on my own in that regard. Like I, you know what I mean? But yeah, like our dynamic was very different, but I don’t think he’s any less of a dad because our approach was different. But if it’s important to you as the mom, then it’s going to be really important to have these conversations with your partner to figure out what is this going to look like. And ideally, troubleshoot it beforehand, right? Although you’ll probably stumble into it.

SHELLY: And sometimes we moms are our own worst enemies, that we gatekeep certain aspects of caregiving, that we feel there’s a right way to put on a diaper, the right way to birth a child. So something that I emphasize in the book is, you know, we have our different styles, safety first, obviously, but then let dads find their own way. And often that’s a different style that research shows is great for kids and brain development. So if they’re more rambunctious or do more zerberts on baby’s bellies during diaper changes, that’s a good thing. And so I think sometimes we edit and especially if we’re spending more time with the baby, we’ll be like, “Oh, well, our son likes it this way.” To not edit so much and to build that confidence. The other thing that I point out in the book is, especially as the kid, I’m just thinking about when your kid goes to school and how often does the school phone tree in case of emergencies or special situations, they call the mom first. And so dad can be first on that phone tree, especially if dad’s a stay at home parent or has a more flexible work situation. Child spikes a fever at school, the dad can be the first to be called. Or birthdays, holidays, who is kind of planning ahead, who’s going to come, who’s going to clean, what part of the house, what’s the food going to be, that can be shared between moms and dads. There’s no reason it should only fall to the female parent. So I try to get really specific and list things that you may or may not have thought of. Like these are the conversations you should have. I’m going to tackle oil changes and car maintenance, but then you’re going to tackle the weekly warehouse shopping and that sort of teamwork. The goal is that if a 4- or 5- or 6-year-old boy watches that, it normalizes it. Just seeing that the male parent is an active caregiver, and obviously this will look different for single-parent homes or kids whose parents are living in two separate households. And in a way that is an advantage because they see that that parent does everything. So they see that it can be done.

DR. AMY: So I want to talk about toxic masculinity. I know that is a buzzword that we hear on the news, and we’ve just heard it kind of floating around for the last few years. And it’s one of those terms that sort of makes me cringe, right, when I hear it. And so I want to talk about that versus aspirational masculinity. Like how we find the balance there. You know, I’m a southerner and I am all about chivalry. And so I want, like, I want to hear like, I want to hear where you land on this, let’s just have that conversation.

SHELLY: I love chivalry. I’m from Chicago and I love it. I think that the issue, and it’s hard to pin down, but the issue with toxic masculinity is that it very much tells our boys and men what not to do. “Don’t this, don’t that.” And it’s interesting because if you have a toddler, if you say “Don’t this, don’t that,” they’ll just, all they hear is the part after the “don’t.” Or how many times do I talk to a family and the toddler’s favorite word is “No”? And it’s like, well, then, you know, we parents, how often are we saying, “No, don’t touch that.” So again, I can’t turn off my pediatrician brain. Developmentally, for toddlers, I’m always recommending to families, talk about what you can do. Like, “Come sit on this chair by me,” instead of “Don’t pull on the blinds,” or whatever the situation is. So similarly, I think the problem with toxic masculinity is it basically is like, “Don’t this, don’t that.” Well, what can boys do? Well, they can be whole people. And they can cook if they want to. And they can be considerate. And they can connect with their friends. And they can share their problems if they’ve had a bad day. So I think that that’s, I agree, I find it so limiting. And sending my three boys to college, my three boys are now 21, 19, 19, my twins, closer to 20, which is a little scary to think about that they’re not even going to be teenagers anymore. But even when they left for college, you hear a lot of conversations guided towards females; how to be safe, make sure that your beverage at a party is always attended to. Are we having those conversations with boys as well? It’s interesting how our coaching for leaving our homes can be gendered. And so it’s a complex topic for sure. And there were situations I would use those opportunities from things in the news is teachable moments. So there was an incident at Stanford years ago where a woman was compromised. And then way later, the judgment came out and the perpetrator had a very light sentence and as uncomfortable as it was—and this individual happened to be a member of the swim team and my kids were swimmers growing up. And so somehow that relatability It’s not pleasant to talk about, but it was something that I brought up with my sons. And I think it can go either way, whether you’re a boy or a girl. You might, unfortunately, have something put in your beverage at a social gathering, and your consciousness may be affected. That shouldn’t be gendered advice. And so, these are tough conversations. Better to have it with you. They’re, your children are exposed to it. I think part of the issue, even when it comes to, you know, school shootings, violence at school, active shooter drills, so many parents I know are afraid to talk to their kids about it. And it’s like, well, it’s early as kindergarten. This is what schools are doing. So it’s happening. And as a parent, you should add your voice to that communication because it’s going to happen whether you’re a participant or not as a parent.

SANDY: I find that that’s kind of like, you know, some of the things that you’re describing, like having these conversations with our kids and you were just talking about, you know, that mental load for us as moms, sometimes we’ve got to figure out that mental load. But a lot of these conversations should probably come from Dad too. Right? So how do we help guide that process? You know, yeah, I would want my spouse, my husband to help guide my son into how to be a man. In fact, any fight my husband and I ever had was usually us butting heads about, you know, his way versus my way of trying to figure out what was best for our son and our daughter too. So could you talk about that a little bit? Because, you know, when I talk, it’s still even now, my kids are 26 and 24. And when Dad speaks, all attention is there. It like comes from a different place. But I talk a lot. And so like whenever I talk or ask questions or I have to, you know, sometimes have these conversations, I can’t do it in the same way. I almost have to wait for them to ask me. It’s a different dynamic that I have with my kids in that case. So, and I’ll talk about that a little bit. How do we get our husbands involved in this? Cause again, that mental load of all, we see everything and we’re always trying to make sure our kids are prepared for everything and all things.

SHELLY: That’s the tricky part because part of the mental load is the remembering to do certain things. And so I take a bit of an issue with the fact that the mom should tell the dad to have the conversations. I think what would work more organically is if there’s the space to have conversations. And a big thing that I developed with raising twins was one-on-one time. Because the challenge all along with having two kids with the same birthday is I feel like they never got anyone alone. And so, and there was, my one son needed stitches in preschool and it occurred to me as he was laying there, getting numbed up for the procedure, my kids never get us alone unless it’s stitches, they broke an arm, they’re having surgery. Like we need a fun reason for them to have their parents alone. So it was then that we realized for each kid’s birthday, they’re going to. choose a restaurant and get Mom and Dad to themselves, which is a tradition that we’ve carried on. And that’s pretty sad because that’s one time of year. Like we could pull that off. It’s once a year. But I think what I’m trying to express here is having that one-on-one time, which leads to those organic conversations. It’s really tough to plan it out. If we, as the parents are like, let’s talk about this. It doesn’t seem to go as well, but to ask open-ended questions and to kind of pick up. And for some boys, I mean, especially in a post-pandemic world, something that I talk about in my book is, you know, if your kid’s a gamer, for example, be humble and learn how to play that game and play with them. It’s humiliating and it’s hilarious. And I think it’s great for our sons to see us try to learn something new. And then if that can trigger conversations, I think it starts first with that one-on-one time together. To then set the stage for those conversations as issues come up, so to make that space available and to that end, to make sure both parents are getting that space, scheduling it in the calendar, like any other important appointment. I think that with COVID, everyone was so happy that our schedules lightened up, and we had more together time, family time. And as a pediatrician, I was really hopeful that that would continue, but at least where I practice in the Chicago suburbs, everyone’s back at it, pell-mell, running from this to that activity. And it makes me a little sad. I think that we needed more of that loose unstructured time. And so then if we’re going to structure that much, then to structure outings. I will say that for one of my twin boys, the best conversations we’ve had is playing catch, which sounds so dorky and simple and innocent, but from a very young age to present day, just to be able to throw either a regular ball or football around, although he always wants me to do like those like pop-ups. I’m sure the neighbors think I can’t play for anything, but I he’s like, “Now they’re only grounders.” Like he wants certain plays. And of course, I oblige, to my own embarrassment, but I’m just kind of quiet and I let him steer the conversation. Because I think ultimately we want, it’s so important for kids’ self-esteem to know what they have to say is valuable and what they have to say is worth listening to. And too often we’ve grown ups are busy and we’re like, “What about this? And have you done your homework? And have you taken out the trash yet?” To make sure that we are self-conscious that we’re not just assigning chores and checking on homework status, but checking in with them as people. Because ultimately, that parent-child relationship is kind of a blueprint for their future relationships. And we want them to have that space to communicate other things, things other than logistics.

SANDY: It sounds like what you’re saying is you want them to be heard. Right? To make sure that they’re heard.

SHELLY: And ultimately as human beings, isn’t that what we all want and need? The connection and to feel valued and heard.

DR. AMY: Yeah. So I love the idea of ensuring that our boys feel the freedom to experience and display that full range of human emotions, right? That we don’t say to our boys, “Well, you shouldn’t feel sad about that,” or “Don’t cry because you’re a guy.” And so I love that. But where do we nurture those gender differences? Where is it okay to say, “Hey, as the guy, you have certain responsibilities when you start dating.” Right? Or like not only around issues of consent, for example, but issues of, you know, who pays? Do you open car doors? Right? Like, do you still show that chivalrous behavior that is traditionally male? Right? Like, so where do we find the balance there of wanting? Yeah.

SHELLY: The first thing that came to mind when you talk about exploring romantic relationships and dating relationships is consent and crazy enough, consent can be taught to kids as young as toddler preschooler. What do I mean by this? When you go to a family gathering and you arrive or you’re leaving, ow often do we say, “Give grandma a hug, give grandpa a kiss”? We want to make sure even our youngest kids are comfortable with that and start to learn the idea of their personal bubble, their personal space. If they want a hug and kiss, awesome. But as parents, to enforce it and make that happen isn’t the greatest idea. And there’s actually wonderful books coming out meant for preschool readers. I’m a big fan of whatever the topic is, an age-appropriate book to explore these issues. Reading with your kids is the number one best thing you can do. So there’s one in particular called “Yes, No. Early Guide to Consent.” And it’s a way to role play different scenarios and things that you’re comfortable with, even including you might’ve been comfortable playing something at the playground and now you’ve changed your mind. And that’s okay. And you’re allowed to change your mind. Because lo and behold, these are the concepts that come up later in romantic relationships. And understanding that if your partner who had said yes to something is now saying no, to listen to that no. There’s also, I think, I’ll just date myself. I’m Gen X. I went to college in the early ‘90s. And I remember going to college and there was a lot of “No means no” conversations. That conversation is shifted and it’s more, “You need an enthusiastic yes. You need an ongoing yes.” So it’s not enough that your partner isn’t saying “no,” they have to be continually and actively agreeing to it. And then holding doors and being considerate, I think that that’s just being a good human being, and it’s showing … when we show our sons that we care about them, we’re modeling how they can act towards their friends, their romantic partners. I will say that growing up, because I kind of was always banging my gender equity drum even in high school, I always demanded to pay my fair share, just because. I don’t know. That was, that was a long time ago, but, and is that right or wrong? I don’t know, because I’ve heard conversations from thoughtful people on the subject that, well, “Women are paid less on the dollar than men. So it makes sense for men to pay because they’re making more money.” So that’s, that’s a tough conversation.

DR. AMY: On who pays? Absolutely. Well, we had a situation in our, in our kitchen about a month ago. And so like, I also went to college in the late eighties, early nineties, and that “No means no” has stuck in my head for decades. My 18-year-old and his girlfriend—I don’t know what they were doing. They were in the kitchen cooking together. And so I couldn’t see them. I could only hear the conversation, you know, where she is saying, “Stop, stop, stop.” And so I don’t know whether he was tickling her. I don’t know. Like I couldn’t see, all I could hear was her saying, “Evan, stop. Evan, stop.” And I lost it. Like, lost my marbles. I turned around. I was in the living room. I turned around and I’m like, “No means no! If she says no …” I mean, I, like, lost it. And they are both standing there like, “What just happened?” Well, anyway, I found out a couple of days later that she was actually egging him on, right? And so like, and she admitted to it being, you know, as much, you know, her fault as it was his, and she just liked getting a rise out of him. And I said, “Okay, but from my perspective, this is what I’m—where I’m sitting—this is what I’m hearing. And I have raised my boys to honor “No.” Right?

SHELLY: And viewing that through an ages-and-stages lens, my perspective is always that it’s easier to teach concepts early because then it normalizes it and it becomes part of your pattern. So when you talk about siblings roughhousing, and if one is saying, “That’s enough,” or even parent-to-child or sibling-to-sibling tickle fest, and they’re like, “Stop it, stop it.” Honoring that request. Or in this day and age of smartphones, I’ve had a few occasions where one of my kids fell asleep in the car and someone’s taking pictures. You don’t be taking pictures without their consent and certainly not sharing the social media, that sort of thing. So consent for, you know, digital images, consent for tickling. There’s so many daily opportunities that come up, and I think the earliest relationship a child has is with their parent, and then siblings if they have it. And then it goes to the teenage, you know. I thought you were going to say he was shredding too much cheese or something. Yeah. And I honestly, I love that.

DR. AMY: I can’t remember the actual story that I should text him.

SHELLY: And that’s also awesome that they were cooking because that’s awesome.

DR. AMY: Yeah. And she’s always bossing him around in the kitchen. Like, ‘cause she doesn’t like how he does it. But yes, she was the instigator. It just didn’t sound that way from the conversation I was overhearing.

SHELLY: Right, for sure. But yeah, my perspective is always planting seeds, knowing that birth to fifth birthday is such an amazing time for a child’s brain development, self-esteem, maturation. And so I’m all about taking action earlier. So, and that’s what the book strives to do. Like, “Okay, now your kid’s in second grade. Now, what do we do? What are the things they need to think about?”

SANDY: So this seems like a good time to kind of talk about platonic relationships with our boys and girls, really. You have some tips for parents about how to help build self-esteem platonic relationships. We’re not talking boyfriends, girlfriends, why don’t you share a little bit about that?

SHELLY: All right, we’re going in reverse chronology. And whether it’s with your, you know, classmates at school, your youth sports programs, religious education. I loved that my kids did club swim growing up and it drew from the whole area and some of their best friends on the swim team went to different schools and I always felt like that kind of bully-proofed them because If they only were with the 20-some people in their classroom, you would kind of think that’s where the world begins and ends, but I feel like it kind of expanded their horizon, so I was always glad for that perspective that they had, that there’s a bigger world out there. The other fascinating thing to me is that boys and girls are pretty equally friends, and then it very much falls along gender lines, and then it opens up again. And I’ve been pleasantly surprised as my kids hit the high school years, how their friend groups were really co-ed. And that’s interesting too, because you mentioned, we’re talking platonic, not romantic. Romantic relationships have changed such that it’s not so much one on one going out but going out as members of a group. So sometimes you don’t realize there’s romantic stuff going on in that coed platonic group outing. But allowing the space for those relationships. As my kids have gotten older, it’s more expensive, but I try, I’ve tried to be the house that people feel welcome at. I feel that then you know who their friends are, you know what’s going on, you hear conversations, or even if you’re driving carpool, that’s when you as a parent hear those conversations. Sometimes if you’re silent up there, they forget you’re there, you hear lots of things. So I highly recommend driving carpool, but allowing those opportunities. And it’s hard because, you know, with COVID, a remote school happened, a lot of activities were canceled. And kids comfort zone now is more texting and social media, even at the younger ages. And so nurturing those in-real-life relationships, having that time together. And I think that’s hard because I have so many kids as young as, well, at all ages, who aren’t sleeping enough. And we talk about, okay, where are you charging your devices? Are you powering down your screens an hour or two before your planned bedtime? And these are things that I think we know we should be doing, but we’re not necessarily doing. But in terms of platonic relationships, I always tell kids in my practice, you know, just make me the bad guy. That’s all my doctor said. I have to turn off my—because sometimes I think kids feel like they’re going to miss out on something if they’re not getting a text or an update or a group chat. So I think that creating that space, but then healthy boundaries as well is key.

DR. AMY: All right. So I want to talk about gender stereotypes that continue to be perpetuated generation after generation after generation. What do you think it’s going to take to kind of break that trend? Things like, why do we paint boys’ nurseries blue and girls’ nurseries pink, and why do we dress them in those colors? Does that matter? Like, why do we buy girls, you know, Barbie dolls and baby dolls and boys trucks and blocks? Like, what is it going to take to kind of blur the lines on those types of things while still honoring real gender differences?

SHELLY: For the book, I interviewed several families, and one of the families I spoke with, we discussed colors, and you mentioned, you know, boy blue color schemes and girls pink, and this particular kindergarten boy, his favorite color was pink. This is before the Barbie movie, because I think this summer, past summer with the Barbie movie coming out, everyone’s embracing their inner pink, regardless of gender. But the expression they shared with me was that colors are for everyone. And I love that. I think, you know, some kids you ask what’s your favorite color and they’ll say rainbow. Because colors are for everyone. So I think as a parent, if your child—one family, I talked to their daughter always wanted yellow shoes and they don’t make a lot of girl yellow shoes. And so they went to a shoe store and the employees kept telling the parent, “Now these are boy shoes, just so you know.” The girl was like first grade. And the mom’s like, “Yup, that’s okay. Like, does that matter?” So that’s, that’s what I mean when I talk about like, as parents, we can have the best intentions, but then you face the rest of the world. So I think just smiling and nodding and being like, “Yup, my daughter can wear yellow shoes or sure. My son can love pink. That’s absolutely fine.” But then also a family I spoke with, the first-grade Valentine’s Day party, the mom purchased rainbow erasers for the classroom, and the daughter looked at it and said, “Well, what are the boys going to get?” And then the mom went through all these layers of like digesting that statement, like, “Oh, no. I’m seeing the patriarchy come out of my daughter’s mouth,” basically, is how she interpreted that. So I think that there’s, I think there’s gender equity. And I think there’s choosing your battles. And I think I would file some of that under choosing your battles. I always think about it in relationship to chores assigned in the home, because I think so often we have our sons mow the grass and we have the girls cooking, for example. We were pretty intentional to make sure our daughter mowed the grass. We have a large space, so it’s a riding lawnmower and some of my favorite pictures of her riding the lawnmower. Not always American Academy of Pediatrics friendly. I won’t say how old she was when she did it. But, my sons, I happen to love cooking and everyone, as it turns out, needs to eat. It’s a life skill. And so from a very young age, I got them involved in the kitchen. And so my 21-year-old has been home this week before heading back to college and I was at work and he made arepas because the recipe was sitting on top of my stack and he thought it sounded good and he had the time to do it. And I thought, “That is amazing.” And when you think about it, some of the best professional chefs are male when you look at like award-winning restaurants around the world. So clearly cooking is not something that only women can do. Like, I’ve never understood, like, why women are expected to cook, but then the best chefs are male. Clearly, boys can cook, so, but the biggest thing is it’s a life skill, and ultimately, when we raise our kids, we’re raising them to have life skills, be able to function independently, including the ability to feed oneself. So I try to focus on those, I guess, more skill-oriented as opposed to the colors surrounding us.

DR. AMY: I love that. Yeah. In fact, all, all three of my boys are great cooks, like great cooks, as is my husband. And so I’ve always worked. Always. And so it had to be something that was a shared responsibility in our house or no one would eat. Like really we’re going to order pizza for the 21st day in a row, right, like if other people don’t learn how to cook in our house, right? I will tell you, I had an incident. I used to run a military boys and girls club, 800 kids, 60 employees. And every time we needed some manual labor done, right, something carried something moved, I would grab a couple of my male staff members to do it. And I finally had one of them come into my office and shut my door and say, “Why do you assume that because I’m male, I can carry all of this?” And I couldn’t believe it. Like it was this “Aha!” moment for me that I never even considered grabbing a couple of female employees to carry stuff or move stuff. I would always grab the first couple of guys that were walking by my office. I mean, I’m almost embarrassed to share that story, but I share it because we do. Like I asked, “Why do we keep perpetuating gender stereotypes?” Well, it’s because of things like that.

SHELLY: And a lot of times it’s us. And owning up to it, we’re gonna make mistakes. And we will make mistakes. And having that growth mindset to identify those spots and to try to do better.

There was an incident on one of my kids’ sports teams where some of the girls were talking about one of the boys in particular and one of the kids pointed out if the genders were reversed, this would not be okay. If a bunch of guys were talking about a girl like this, you’re objectifying him. And it was such a, there’s so many times where grownups might brush it off like, “Well, that’s just, you know, how they are.” But it’s not okay. There’s certain situations that somehow we adults are okay with it in one gender direction, but not the other. And so being self-aware, being open. And kudos to you for being the sort of person that that individual felt comfortable speaking up to because that you created a space to, in which to have that conversation. And that’s important. And I think that’s the huge, that’s a big theme of mine, like create the space for those conversations because our kids will inform us, especially Gen Z. I feel like there’s so much smarter than the rest of us on so many issues. And I think we adults all too often, we’re, we think we got it all figured out. No, we need to listen. Somebody smarter than me said that, “By the time your kids hit 12, they already know our parents, their parents opinion on everything under the sun.” That’s when we need to talk less and listen more. Also, because they’re about to leave us. Those final high school years are like lightning fast. And so, it’s like the launch pad and it’s the basis of the rest of your relationship as they embark on their lives.

DR. AMY: Alright, so, um, we need to take a break. Let Sandy read a word from our sponsor. And when we come back, we will, uh, wrap up with any final thoughts.

SANDY: Are you concerned about your child’s reading or spelling performance? Are you worried your child’s reading curriculum isn’t thorough enough? Well, most learning struggles aren’t the result of poor curriculum or instruction. They’re typically caused by having cognitive skills that are, um, they’re typically caused by cognitive skills that need to be strengthened. Skills like auditory processing, memory, and processing speed. LearningRx one-on-one brain training programs are designed to target and strengthen the skills that we rely on for reading, spelling, writing, and learning. LearningRx can help you identify which skills may be keeping your child from performing their best. In fact, we’ve worked with more than 100,000 children and adults who wanted to think and perform better. They’d like to help you get your child on the path to a brighter and more confident future. Give LearningRx a call at 866-BRAIN-01 or visit LearningRx.com. That’s LearningRx.com.

DR. AMY: And we’re back talking with Dr. Shelly Flais about her book, “Nurturing Boys to Be Better Men; Gender Equality Starts at Home.” So Dr. Fleiss, talk to us a little bit about some of those phrases that just come flying out of our mouths, like “boys will be boys.”

SHELLY: That’s the worst.

DR. AMY: Why? Why is it the worst?

SHELLY: You started with my number one. Well, at a family gathering, when my three boys—all born within 18 months—were small, all the boy cousins were just kind of running around and all the grownups were standing there saying over and over, “Boys will be boys.” And I thought, “What a limiting statement.” So we’ve just thrown this whole gender under the bus. Like, they’re just rambunctious, they’re not analytical, they’re just, it just, I feel limits. Kind of like toxic masculinity, it limits what our boys can be. And so what’s hard with families is you’ve got different generations and you’ve got different layers, aunts, uncles, et cetera, and you can set the tone. And it’s interesting because over the years, especially as your kids get older, it’s okay to have frank conversations and your kids are smart. And they are going to notice that certain branches of the family operate differently. Or even within their friend groups and they socialize more and their friends’ family structures look different or have different goals and priorities than yours. I found myself saying, I don’t know what grade it was, but I say, “Well, in our family, blah, blah, blah.” Because it’s just, there was always things going on. Even, you know, I’m a pediatrician, so I’m all about car seat safety. And at a very young age, a lot of kids were already. No car seat in the front seat, well below the legal age in Illinois. And so my kids would be like, “Why can’t I just write in the front seat too?” And I’m like, “Well, in our family, we believe in safety.” And also, and I would say things like, “You don’t want mom arrested, do you?” And sometimes you’d be like, yeah.

DR. AMY: Oh, yes. Oh, yes. You can’t use that one because like, I can’t tell you how many times my kids would go, “I’m calling social services, Mom.” Because I would say, “Hey, they’ll call social services on me if I let you do that, right?” And so then they’d turn that around and weaponize that, you know, for me.

SHELLY: It became a catchphrase.

DR. AMY: Yeah. Like, if you do this, I’m calling social services. Or they’ll yell, “Child abuse!”

SHELLY: And that in and of itself underscores the power of words. And so, in terms of “Don’t cry” or “Toughen up,” I mean, even in youth sports teams, very quickly, I heard “Toughen up” or “Man up” is another one. I just, and so you might be aware that the coach said it to your son. And so to have a conversation about it. And open-ended questions like, “How did you make that feel?” or “Do you feel that it’s, you know, wrong to cry?” You know, just to ask questions about it to give your child the space to be analytical about it. I think one of the challenges of childhood is you trust the grownups around you. I know when I was a kid, I just assumed adults had it all figured out. Lo and behold, I’m an adult. Now I know we’re all just winging it, doing the best we can with our circumstances present at the time. And so, I think that when your child goes forth into the world and hears certain things from a coach or different scenarios, to give them the ability to explore that and to know that they too should have a growth mindset. Or to identify that there’s adults out there who could use a refresher on their way of looking at the situation. And you don’t need to forgive, you know, you can be respectful to a coach and be true to your sports team, but then not agree with the way something was communicated. And so having those conversations, I think, is part of it. And then, God forbid, if something were inappropriate of, you know, as the kids get older, if there’s some hazing or abusive situation, you want your son to have the space to speak up. There’s plenty of cases, and even the professional sports world, where male victims have come forward later to talk about how they were compromised, and it’s still taboo. And people even think, “Well, it’s a guy, why are they worried?” Which is, they’re human and they were violated and that, and that should matter. So, and that starts in the young ages and I think that starts with those expressions. So boys will be boys, boys don’t cry, man up, toughen up, boys don’t X, Y, Z. No. And it’s, even if you’re, you know, one family I talked to the grandparents were like, “Well, what should we get them for the holidays?” And they had two young boys and the mom said they would really love a play kitchen. They would think it was the best thing ever. And the grandfather was like, “Really?” He’s kind of like, “Aren’t you going to play with trucks and cars and things like that?” He obliged and was shocked at what a resounding hit it was, and God bless him, had, you know, he’s obliged with the parents’ wishes and then saw for himself that that was definitely the right move. And so, and we, and when we have family like that, awesome. We may not. The beauty of humanity and our relationships with each other, because somehow we can love our family members but not necessarily agree with all their choices, their decisions, their ways of being.

DR. AMY: We had a play kitchen for our boys, and it was like, that play kitchen was probably the most used part of our playroom when my boys were little. So that’s probably why they all cook now, right? Because…

SHELLY: And because their dad role modeled. It sounds like their dad was role modeling and normalizing it. So, and that matters. That’s huge. If they can see it, they can do it.

DR. AMY: I like that. Any last thoughts that you have for us, Dr. Flais?

SHELLY: So a big theme of mine is connection and connection will look different when your child is an infant versus 5 years old versus 12 years old. And so one might look at the title of the book and think, “Oh, well, she has an issue with men.” I love being a mom of sons. This book is very pro-boy, which is a really weird way to phrase it. I want boys to be whole, complete people. I want them to feel connected. And so bottom line, we kind of plow through the ages and stages and talk about how parents can nurture that in their boys. And then it’s win-win, because when they’re decades later, able to communicate, reach out for help when they need it, it boosts their mental health. It’s men and women similarly will benefit. So I hope that you enjoy the book.

DR. AMY: Absolutely. All right. This has been a fantastic conversation. Thank you so much, Dr. Shelley Flais for coming in, talking about your book, your passion about what it looks like to raise boys in this world today, right? How we don’t have to do it the same way we’ve done it for generation after generation after generation to really honor the whole child who then becomes the whole man, right? Exactly. Listeners, thank you so much for joining us today. If you would like information about Dr. Flais’s work, you can connect with her on Instagram and Facebook at— Oh my gosh. My contacts just fogged up.—Shelly Vazir Flais MD. That’s s h e l l y v a z i r f l a i s m d. And on Twitter at Shelly Flais MD. We’ll put those links and handles in the show notes o that you don’t have to go back through and blend all of those sounds that I just linked together. Thank you so much for listening today. If you liked our show, we would love it if you would give us a five-star rating and review on Apple Podcasts and follow us on social media. We are on every single platform at The Brainy Moms. Do it right now before you forget. You can also find Sandy on TikTok at The Brain Trainer Lady where she has just some amazing, fun videos that are always so impressive to me. Hey, if you would rather watch us, we’re also on YouTube. That is all the smart stuff that we have for you today. So we’ll catch you next time.